Plagiarism features prominently in The New York Times’ landmark lawsuit against OpenAI and Microsoft*, citing many instances when Chat GPT spat out Times articles verbatim in response to prompts.

In my writing on the topic, I’ve questioned how much this evidence really matters. While giving word-for-word copies of articles as answers looks pretty damning, it happened only in response to very specific prompting. In any case, OpenAI seems to be patching ChatGPT in real time to avoid giving these kinds of plagiaristic responses. Yes, damages still matter to the courts, but in the context of future usage, OpenAI could make the case that the problem has been “fixed.”

However, the other side of the argument — that plagiarism is still a serious concern in the use if AI — is explored at length in this riveting article in IEEE Spectrum by Gary Marcus and Reid Southern. The pair take a thorough look at how generative AI-powered image generators like Midjourney and OpenAI’s DALL-E sometimes, perhaps often, produce copyright imagery in response to prompting. Sometimes just a single-word prompt could produce images that look lifted directly from Marvel movies like Black Widow.

The existence of plagiaristic output from AI systems amounts to a confession of sorts: That the AI’s training data included copyright material. After all, how would an image generator even know to replicate Scarlett Johansson as Black Widow if it never “saw” an image of her as that character in the first place?

That leads directly to the chief legal question: Is the nonconsensual harvesting of copyright material for training data (standard practice when all web crawlers did was index for search) OK? Everybody has their own opinion on this, but we don’t yet have a legal answer. The New York Times’ lawsuit looks like our best shot at one.

The Pragmatic Concern for Editors

But the more immediate and pragmatic concern for content creators and especially newsrooms is: If some kind of prompt will lead to a plagiaristic result, what assurance can a user have that any response you get isn’t plagiaristic?

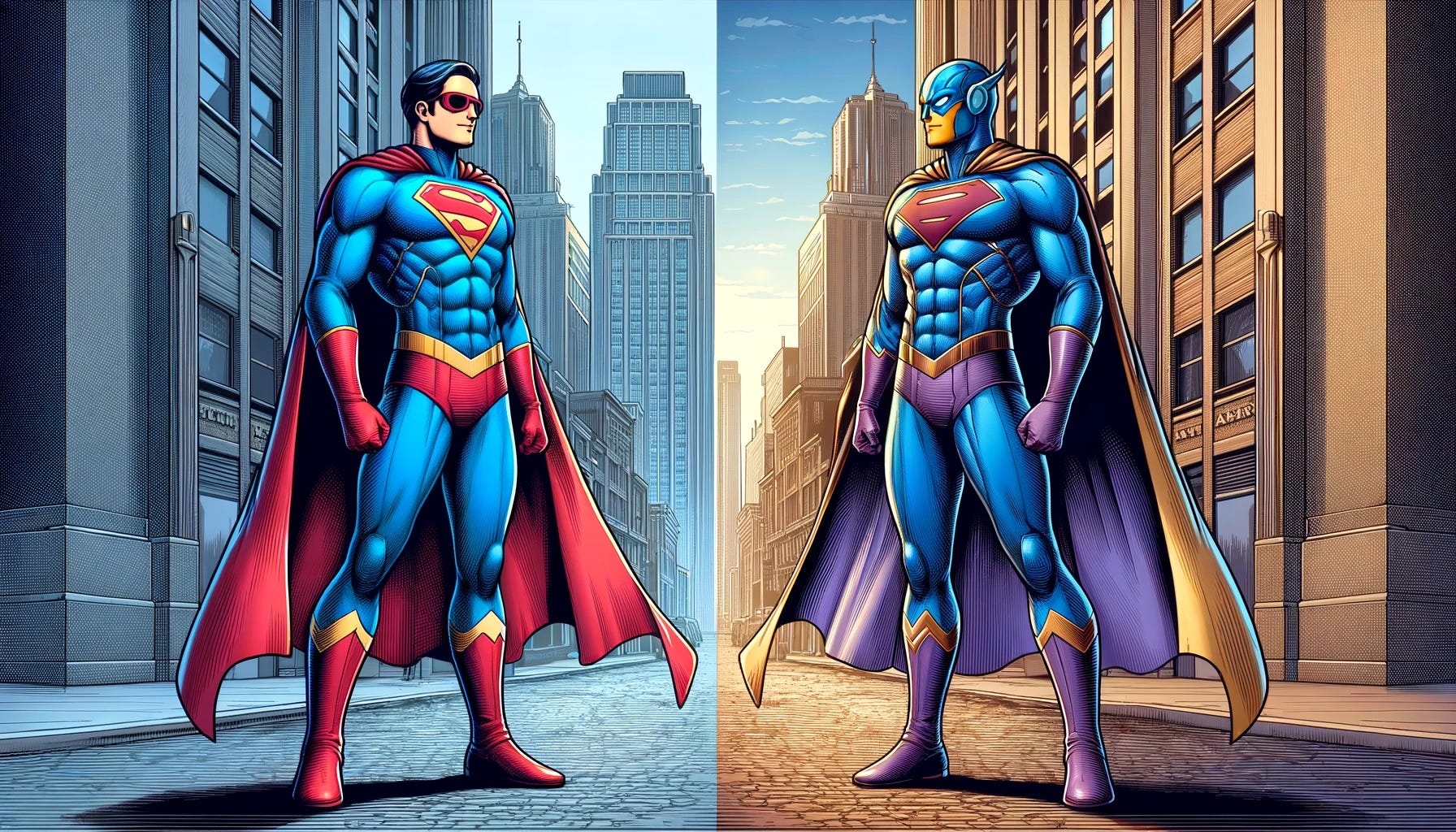

Marcus and Southern’s analysis provides good guidance in how to think about this. They give several examples of instances where AI generators created images that were close — but not exact — duplicates of stills from popular movies.

Because those images aren’t pixel-for-pixel recreations, it makes outright plagiarism difficult to spot from a user standpoint. A Google Reverse Image Search is basically useless.

Certainly, we all know what Iron Man and other popular characters look like, so obvious copyright violations will be easily spotted. But what if the AI serves up an image of a much less well known superhero, possibly from an independent creator? How would you know whether the AI had created something original, or merely copied someone else’s work? That’s much more difficult to spot, but the potential for a copyright violation, and the associated legal exposure, is just as problematic.

As these copyright issues continue to percolate in AI image generation, it can only benefit services like Adobe Firefly, which claims to be trained only on licensed or public-domain content.

What About Text?

So, the copyright of the output of image generators can be a concern. If you’re an editor, the next logical question is: Are text responses from LLMs like ChatGPT just as susceptible to plagiarism?

Intuitively, you would think yes. At a basic level, these models work very similar to image generators: provide users with the best output that aligns with the prompt, and how they come up with those outputs is just as mysterious. Add to that the evidence of the Times lawsuit, which effectively shows ChatGPT caught red-handed plagiarizing, and you might conclude LLMs copy answers from their training data regularly.

However, we should draw a distinction between an output that is serving up training data verbatim, and one that is creating new output. In most of the instances of plagiarism that the Times cites in its complaint, the prompts weren’t general queries for information — they were designed to elicit the verbatim text of the articles themselves.

There have been other instances where LLMs output what looks like training data unexpectedly. In my recent conversation with Lee Gaul of Copyleaks, which is an AI and plagiarism detection service, he noted that, “There actually is the ability for language models to divulge training data. It’s a complex thing because I’m not sure if that stuff is purely plagiarized data from the training set or if it’s an approximation of the training data.”

In both cases, though, the prompting is very atypical — not your everyday query.

In addition, the process of scanning copy for plagiarism is much more established, and thus is theoretically easier for AI companies to guard against. Practically, it would be straightforward to simply add, “scan for plagiarism” at the tail end of a text output. That might explain why, after reports of plagiaristic AI-written articles in the early days of 2023, it hasn’t come up much since.

Is that enough to assuage editors’ plagiarism fears? I expect there are a few too many assumptions about what’s happening in the prompt-to-output process to erase them completely. However, if the creators of LLMs made clear what they were doing to eliminate (or at least reduce) plagiarism, it might help adoption of the tech by a litigation-averse client base. That, however, will likely require a judge to tell the LLM creator that it was OK to harvest the data in the first place.

And… we’re back in court.

*Disclosure: Members of The Media Copilot team do consulting work for several companies, including Microsoft.

We have a new meetup group for The Media Copilot. We’d love to meet you in person. If you’d like to be a sponsor for the meetup, please reach out to team@mediacopilot.ai. Otherwise join the group and let’s all get together!

Leave a Reply